Winter 2014

Zombies are everywhere! They are ubiquitously found in books, movies, comics, video games, TV shows and on the streets (zombie walks). What’s with all the zombies? What is the significance and meaning of zombies in our culture? Zombies are saying something to us about us—but what?

In my pride and prejudice (something no scholar should have!), in my ignorance, my initial critical assessment was (watching my son play Call of Duty Zombies): “I don’t know if the zombies are on the screen or behind the controls”. Or as one of my son’s online friends put it: “Every game has #@$%*@#* zombies in it—whoopty doo”! That, of course, expresses a doubt that there is much original or interesting or even good art to be found in zombie culture. Like my son’s friend (my son is naturally like this too): I am resistant to any popular trends and treat them with the utmost suspicion and scepticism—something all good scholars should do.

But even Timothy Madigan, in an editorial for Philosophy Now, had to begrudgingly concede the centrality and significance of the “Zombie Invasion of Philosophy”. Indeed Zombies are a complex reflection of who we are as individuals and culture—which raises very serious issues and questions. Zombie culture is telling us that life is a great big profound mystery—larger than any one of us as an individual. Actually, I think that zombies are a much more intelligent, deep, sophisticated and multi-layered metaphor for many of the struggles we are encountering on both an individual and societal level—even eclipsing Mary Shelley’s classic Frankenstein (and that’s good art!).

Irony is intrinsic to zombies: We can either be a victim of them or critically enlightened by what they are saying. So for example: If we are not thinking about what zombies are saying, we ironically end up a zombie with thoughtless, ceaseless and meaningless activity. This ceaseless activity also has the effect of desensitizing and numbing us eg to violence or purchasing. If we critically engage zombies as scholars, we will be blown away by the depth of questions and issues they raise. There are so many examples that I could explore in this article—but I will limit to a few.

My recent journey to zombie enlightenment began by watching my 16 year old son playing Call of Duty Zombies. Given that he is a lot more intelligent than me, I should have known that he knew something I didn’t. Then I heard a voice while driving in the vehicle with my son: A divine voice ironically infused in the death metal of COD Zombies—the voice of Elena Siegman. This in turn led me to the musical genius and mastermind of the COD Zombies music: Kevin Sherwood—who will be our keynote speaker at the Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith 2015 conference on Religion and Pop Culture.

As already noted: Zombie culture is intrinsically ironic eg they are the “living dead”. Sherwood masterfully conveys this irony and the anxiety of our existential angst by employing the Doctrine of Ethos in his music. The Doctrine of Ethos is a Greek philosophical concept that says that the music must “embody the idea or theme it is trying to convey and produce an effect on the listener”. This can be heard in the COD Zombie Canon—music composed for Call of Duty Zombies. Irony can be heard in Sherwood’s employment of Elena’s angelic voice emanating out of the genre of death metal and the anxiety of our existential angst in the “haunting effect” that won’t leave the listener alone. I am haunted by this music and its ideas as I listen to it on the way to work—and it haunts me all day long—and has done so for over a year now . . . .

Based on the Creation Theology of Genesis 1, I see theological analogies with Sherwood’s COD Zombie Canon—and its all good! Taking matter that God has already created (Genesis 1.1-2), Sherwood brings order (by the structure of his music) out of chaos (the zombie apocalypse). He brings beauty out of ugliness through his music and Elena’s voice eg the “Beauty of Annihilation”. Sherwood brings good (art) out of the evil of zombies. This is an example of how critical analysis enlightens us to profound ideas and beautiful art (including the graphic design of COD Zombies)—if we are, as scholars, open to learning.

Another prime example that explores the complexity of zombies is AMC’s The Walking Dead and Talking Dead. Talking Dead is a weekly debriefing of the episodes of The Walking Dead by guests from all walks of life. As an educator, I said to my wife and son last weekend that what excites me most about Talking Dead is the fact that The Walking Dead generates so much thinking, analysis and dialogue from all kinds of non-scholarly people in our culture. It means that people are thinking and talking about the big questions and issues! They are not becoming the ironic victims of zombies and watching “mindless” entertainment! They get it!

Marilyn Manson, in a recent TD, said that The Walking Dead is not about zombies: Its about “morality”. While I am sure that he would not agree with my take on it, we are a morally conflicted society who intuitively know that our views on morality are not working very well for us. Rick struggles with this very issue personally and as a leader. As a pastor, I see this moral confliction every week as students come for pastoral care—often related to the breakdown of the family and or romantic relationships—something for which I have nothing but compassion.

Adam Savage from Myth Busters made the point in TD that the prison in season 4, which has kept Rick’s community safe and secure for a while now, is actually a metaphor for us in society. As the prison walls teeter from the outside (representing external threat), a virus is killing survivors from the inside (representing internal threat). Savage comments that this really reflects our delusion: We think that we live in a stable society with a stable government. But intuitively we all know that governments can collapse (as reflected in the recent shut down of the US government) and put us into chaos. That is what the apocalypse represents: The breakdown of order into chaos—the reversal of Genesis 1 and the effect of Genesis 3 as ultimately reflected in the Book of Revelation. Even if we do live in the security of the prison, individually we can die from infection. The prison metaphor really represents the bondage that we are all in regardless of where we are: We are all trapped by circumstances whether we admit it or not. No one is safe nowhere at no time: Death is a clear and present danger for us all—and that’s what zombies represent. Moreover, zombies question whether we’re really free at all (individualism) or are we all the victims of circumstance (determinism)?

Christianity is represented in The Walking Dead throughout. We see theological questions raised about theodicy (“justice of God”), faith, hope, destiny and purpose. Hershel is a Christian man—with wisdom, grace, compassion, guts and practicality. In season 2, Hershel asks Rick if he believes. Rick answers that the last time he prayed to God about his son, he walked out of the church to the sound of a hunter accidently shooting his son and nearly killing him. Many of us have struggled with the unfairness, evil and hurt that life in the world can bring us. Rick and his confliction and lostness (is he a farmer or a cop?) represents this acutely in TWD.

In the episode Internment, Hershel raises the leitmotif of destiny, purpose (reason) and meaning with Rick. He tells Rick that no matter how bad the chaos, destruction and death, there has to be a reason for it, a higher purpose (meaning)—and that we need to persevere. Zombies represent the relentless pursuit of evil leading to death. Or as Sherwood puts it in his song Beauty of Annihilation: “They’re all around me. They’re waiting for me . . . . Descending. Unrelenting”. Perseverance is another theme in zombie culture—as reflected in Sherwood’s song Abracadavre: “I can’t give in. I won’t give in”. Hershel says that, no matter what, we must go on in life and hope for a better afterlife.

Indeed, meaning is yet another idea that The Walking Dead raises. So what if we survive the apocalypse, is there any meaning to living like this—killing, stealing and scavenging just to survive? Many people ask this of their 9-5 job. Are we any better than the zombies? Or do zombies actually have it better by not being conscious nor feeling any pain? These are questions that The Zombie Invasion of Philosophy in Philosophy Now asks. Sherwood asks in one of his songs “Where Are We Going [in life]?” . . . .

Hershel also represents hope and faith in The Walking Dead as noted in the Talking Dead. In Internment, we see Heshel’s courage and strength as he treats the viral patients and watches them die and change into zombies. Darrell comments that Hershel is a “tough sombitch”—to which Hershel replies with wise confidence “I am”. Hershel has a deep love and compassion. He hates death and killing because he is a life-affirming believer and “healer”. In season 2, he held out hope for a cure to the zombie virus in relation to his loved ones in the barn. Nonetheless, as he sits on his prison bed, after a long shift of rounds, he opens his Bible to read it—but breaks down and can’t.

Savage in TD wonders if Hershel is losing his faith and if the zombie apocalypse has finally worn him down. Being a scholar of biblical wisdom, I don’t see it that way. I see parallels with Job—a man who is in an acute faith crisis because of all the chaos and suffering life has thrown at him. Yet he never gives up on God and what he believes. He doubts, questions and rails on God but he perseveres. Job and Hershel are not in denial about the chaos, suffering and death they are experiencing in the real world. Hershel and Job are realists who are intelligent enough to understand the issues—but brave enough to keep on going. I view Job as a “tough sombitch”.

I also understand the problems that people and our society have with Christianity. But I am unwilling to surrender to the darkness that I view has only partial truth and is ultimately a “dead end”. Intuitively zombie culture knows that there’s got to be something more to life in the material world—and that there has to be some kind of “after life”. Or as Sherwood puts it in his song Where Are We Going?: “Where do we go [after life]?” I think that there is a clearer and better explanation for reality that is not limited by the material world but is found in metaphysics—and specifically the Christian Faith.

As a Christian interpreter of zombie culture, I see zombies as a reflection of our deep internal struggles with the big questions and issues of life and death. To quote Sherwood again: “How do we know?” This question inherently raises issues about epistemology: How much we can know and how do we know what we know? . . . .

Essentially I think that zombies are an intuitive reflection of the Fall in Genesis 3—divinely revealed in Scripture (how we know)—but existentially (theologically) experienced by all human beings (reality). What zombies are really all about is Original Sin that brought chaos and death into the world. Zombies reflect our sinfulness and the ugliness from within (low self-esteem based on moral wrongs) and without (chaos, death and destruction in the world). They represent a “living hell” of our own making. Zombies reflect our obsession with death and deepest anxieties and doubts about where we go after we die. The Book of Revelation calls this the “Second Death” or the “living dead”. Unlike Revelation, there is no Gospel of Zombies—just death, destruction and meaninglessness. Zombies are a “dead end”. But the Book of Revelation promises a “new heaven and a new earth” with a resurrected body and eternal purpose.

My bottomline analysis is that zombies are really all about our intuitive need for a Savior and eternal life. We are in a living hell of our own making—and we can’t kill, steal, scavenge or think ourselves out of it—and we know it! We have an intuitive knowledge of this truth vis-à-vis the Fall of Genesis 3—and that is why we are so anxious and hopeless in a dark and ugly world represented by the prevalence of zombie culture.

The anxiety of who we really are, and how we are a part of the problem (including our denial), is reflected in Sherwood’s song Always Running: “I’m running from the something that I’m coming from . . . . and becoming one means I’m running from all I am”. In my view, the something that we are always running from is Original Sin.

The church, while historically very flawed, is really the community that people are looking for—not the prison of our own making in The Walking Dead. It is the only real community who together will survive the apocalypse eternally. Because even if we survive the apocalypse in the material world—we all have to die—and then what? The church is “living living” that transcends our historical and sinful nature by faith—full of meaning and purpose in this world—who will rise again from the dead to the resurrection of eternal life.

This we see in Hershel in The Walking Dead. Hershel dies in the most violent way with a smile on his face and peace in his heart—knowing that he had lived a meaningful and purposeful life with full assurance of the resurrection unto eternal life. He lived and died this way all because of his Christian Faith based on the atoning death and resurrection of Christ.

Jesus created us and wants to redeem us. Jesus, like Hershel, died in the most violent way in the context of the evil of religious, cultural and political chaos. The ugly irony of the cross brings sense out of senselessness, purpose out of evil, clarity out of confusion, order out of chaos, beauty out of annihilation, atonement for sin, and life out of death. Jesus said that “I am the Way, the Truth and the Life”. Jesus is the Answer people are really looking for as reflected in the questions and issues of zombie culture.

]]>Bill Anderson PhD

[email protected]

Religious Studies

Winter 2016

I always wanted to be an atheist. I didn’t grow up in a Christian home. I grew up in a working class Scottish home with lots of love, many benefits and much happiness! No philosophy was more drilled into me than this: Be your own man. Stand on your own two feet. Do your own thinking. And don’t let anyone influence you—no matter who they are. Being an atheist is the ultimate Scottish working class philosophy.

When I got to my mid-teens, I started to philosophize about many things more seriously. I especially tried to figure out how I could reject any concept of God. But I got stuck. My limited knowledge of the universe led me to one firm conclusion: The universe is extremely complex and delicately balanced—and could not have just “happened” by itself through numerous coincidences. This was an irrational idea that I could not intellectually accept.

Of course, at the time, I didn’t know that its technical reference was the “Teleological Argument from Design”. The Teleological Argument from Design is, in my view, the most powerful argument for the existence of God.

Another argument that forced me to reject atheism was the Cosmological Argument. While I’m an “arts” person, I do know that for every effect there is a cause. This means that the universe must have had a First Cause, i.e., a Creator. I know that both of these arguments have been sorely tested in recent decades.

By the way, I don’t pretend that my arguments are as sophisticated as say, Professor Richard Swinburne of Oxford University, who will be our keynote speaker at our 2016 conference on “Atheism and the Christian Faith” here at Concordia University of Edmonton on May 6th and 7th. But they are so substantial and forceful that I cannot reject them on rational grounds.

However, these arguments were not enough for me to become a Christian: You can’t argue a person into Heaven. The question then became: Ok, now what? There must be a god, a creator, but he cannot be “personal”. I based this on the problems of evil and suffering, as well as unanswered prayers in my own life. Therefore a person cannot have a “personal relationship” with God. It took a literal, miraculous “Damascus Road” conversion experience on a construction site before I “saw the light”. Or as Jesus puts it in John 3: A person must be “born from above”, i.e., by the agency of God’s Holy Spirit.

Nevertheless, that’s not the end of the story. My faith has been tested many times over the past 36 years that I’ve been a Christian. As a pastor, I’ve never really fit in the church, seminaries or denominational offices. Moreover, I did my PhD under the atheist biblical scholar Robert Carroll at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. I learned a great deal from him and I am eternally grateful to God for him (though he wouldn’t view it that way).

As a professor, a recurring question that I ask my students is: “When the atheist reads the Bible, they are objective—true or false?” My response is that its “so false I can’t even begin to tell you”! Atheists, being human like myself, have baggage and are often prisoners of their emotions with political agendas too—and these will skew our interpretations of texts and lead to Confirmation Bias.

Confirmation Bias says that we will find what we are looking for regardless of the evidence or we will interpret the evidence in the light of our own biases and without full context or openness to alternative positions eg atheism. Psychologically and emotionally, atheism suits me: I just can’t make a rational case for it. That is the necessity of keeping our emotions out of it and employing objective protocols when doing academics—especially in biblical studies. Because if Christianity isn’t objectively true, then I want out: It’s not worth the hassle and humiliation in today’s society.

Of course the title of my editorial is a pun on Bertrand Russell’s classic treatise on atheism entitled “Why I am Not a Christian”. But I think Andy Partridge says it more concisely and powerfully in the XTC song/video “Dear God”. In both works the “usual suspects” are rounded up as insurmountable problems to theism and the Christian Faith: Problem of Evil, Innocent Suffering and Theodicy (Justice of God or life isn’t fair). Russell also attacks the Cosmological and Teleological Arguments in his treatise; where he ironically falls acutely into his own criticism of reductionism and lack of imagination.

These problems can be summed up in Epicurus’ syllogism “Inconsistent Triad” which is picked up by the Scottish philosopher David Hume in DialoguesConcerning Natural Religion. There are many variations of this syllogism but it basically goes like this:

1) God is all-loving but not all-powerful; or

2) God is all-powerful but not all-loving.

3) Because evil exists, there cannot be a perfectly good, all-loving and all-powerful God.

I am totally empathetic to these works and the problems they raise. However, existence, reality and theology are far more complex than this simplistic and reductionistic syllogism. But, as a PhD in Old Testament Theology, I know that there is no biblical answer to these genuine problems.

As a pastor, however, I practice “Lived Theodicy”. I agree with the atheist’s legitimate complaints and simply come along side suffering people and empathize with them. I also know from the Book of Job and the example of Jesus that our sufferings are meaningful and purposeful. Indeed, all my sufferings in life have given me the experience and empathy to minister to people deeply.

Having said all that, my faith is not based on what I do not know. I don’t believe in blind faith. I know that I don’t know much as a human being vis-à-vis an all-knowledgeably wise God. So my reasonable faith puts these problematics into suspension until I am received into the Absolute.

My Christian Faith is based on what I do know about God. I know that there is a Creator and the evidence of the universe supports the Three Os of Theology Proper: God is omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent. The Three Os are also reasonable grounds for the belief in miracles. I know that God is LOVE from the Bible (1 John 4.8), the example of Jesus and by living life in this beautiful creation (with all its downsides as well). I know from theology that God is holy (perfectly moral) and therefore cannot be unjust or unfair. I know that the Gospels are eyewitness historical documents as verified by archaeology (contrary to the very trendy and naughty documentaries to the opposite that are often based on conspiracy theories). I know that God became human in the form of Jesus and that the Gospels documented his good person, life, death, burial, resurrection and ascension. This eyewitness testimony is a substantial basis for Christian Faith. That is why I am not an atheist and why I am a Christian.

TECHNOLOGY AND THEOLOGY

Bill Anderson PhD

Director of the Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith

[email protected]

Winter 2019

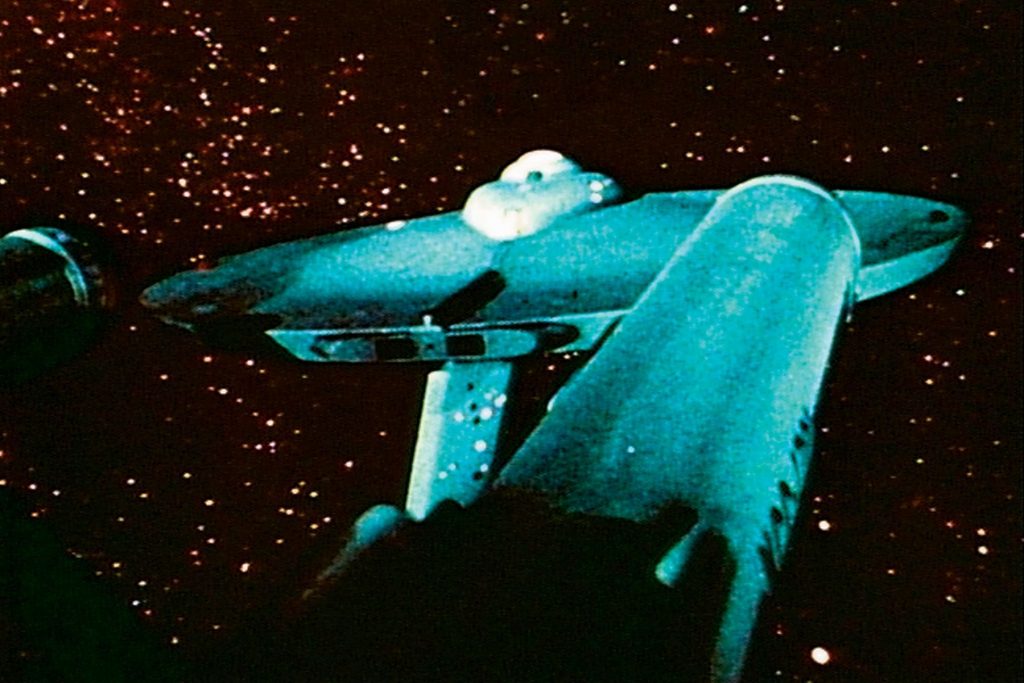

“Space, the final frontier. These are the voyages of . . . .”. My first foray into technology was watching Star Trek in the 1960s. I was only 5 years old when it originally aired in 1966. But when ITV Edmonton did re-runs in 1975, I was totally hooked and obsessed. Now my wife Joan and I spend 5 or 6 hours a week in the deepest, outermost parts of the galaxy.

Before we go any further, I want to make a disclaimer. I am neither a scientist nor technologist. I am a trained biblical scholar and theologian who teaches extensively in the area of Pop Culture Studies. I am currently developing a course Technology, Philosophy and Religion and the course description reads in part: “Basic introduction to Technology with an examination of philosophical and religious ideas, themes and imagery in, and with an emphasis on the ethical dilemmas conveyed and posed by, the portrayal of technology through pop culture and specifically in the genre of Science Fiction literature, film and television”. So this is the way that I am addressing the topic of “Technology and Theology” here in this editorial.

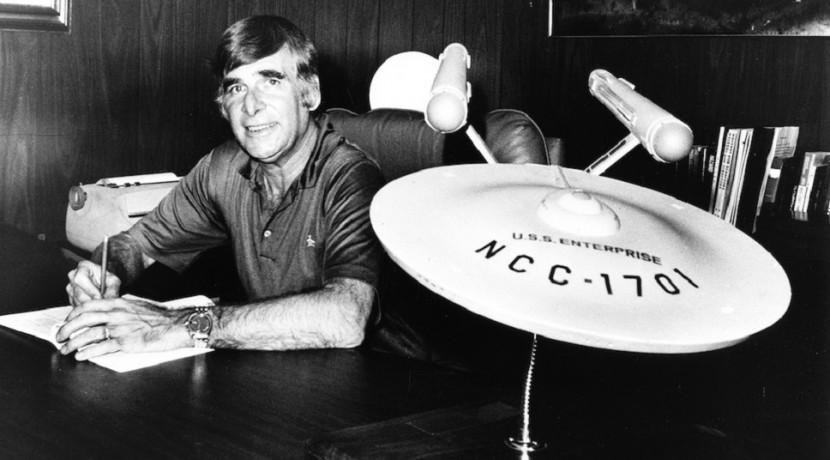

Now back to Star Trek. Gene Roddenberry originally pitched the series to the networks as a “wagon train to stars”—picking up on the other cultural obsession with Westerns in the 50s and 60s. As any student who has taken one of my pop culture courses knows, every artifact is a reflection of the artist’s philosophy, beliefs and values, as well as the cultural milieu in which it is situated.

Roddenberry was a complex man with a complex relationship to theology and religion. He grew up in a Southern Baptist home in Texas and was very involved with church activities. He later rejected the faith when he was around 14 years old.

Often Roddenberry has been portrayed as an atheist. Later in life he asserted that he believed in some concept of God (a form of deism) but categorically rejected any notion of organized religion. My own analysis of Roddenberry’s philosophy is that he appears at certain points to function as an atheist but always as a secular humanist. I think his complex relationship with technology and theology can be seen the various manifestations of the Star Trek franchise.

In the original series, Roddenberry’s atheism, or perhaps more accurately secular humanism, was more sublime—even though in public discourse he could be quite harsh against organized religion. I speculate that this may have been because it might have damaged ratings if it was overt during a time when religion was still well-regarded and widely practiced. Yet the concept of God or spirituality have been a mainstay of the Star Trek franchise throughout.

Roddenberry gave strict instructions that Star Trek: The Next Generation was to be thoroughly secular—and that there was no place for religion, superstition and mysticism. But Star Trek betrays subtle cognitive dissonance between science and religion: It can’t seem to get away from religion and even at times portrays it in positive ways. Star Trek Deep Space Nine is a case in point—where an abundance of overt religion, spirituality and mysticism can be found—although often with the intent to portray it as primitive, emotional and unreasonable.

Religious themes, ideas and imagery are found throughout all Star Trek series. See an excellent little summary in Ex Astris Scientia at https://www.ex-astris-scientia.org/inconsistencies/religion.htm. This relates to one of my own obsessions: Non-religious artists (particularly in the science fiction genre) who are obsessed with religion and religious themes, ideas and imagery reflected in their art. Roddenberry is no exception in the Star Trek franchise. Ridley Scott is another one.

The current Star Trek series Discovery perhaps is a re-assertion of Roddenberry’s original philosophy—complete with a superficial and stereotypical portrayal of ignorant and backward Christians—in the episode “New Eden”. Here the superiority of reason and science (scientism) is strongly asserted by the Science Specialist Burman—complete with buy-in that “technology saves all”. But even in that episode, doubt is cast upon the totality and efficacy of science and technology over against the mysterious and faith as masterfully conveyed by Captain Pike’s framing of the issues.

Roddenberry and Star Trek, along with atheism, have a major problem to solve. Or as the website Ex Astris Scientia puts it: “The question crops up whether Star Trek’s philosophy can offer anything to replace religion?”. Yet the irony pointed out in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is that science and quest (“voyage”) ultimately lead to a Creator God: Science and Technology intersect with religious experience. This can also be found in Star Wars.

Modernism is the broader philosophical background to Star Trek OS. Rodenberry’s Utopian vision was based on the idea that science and reason could solve all of our problems. There would be no more hunger, disease or war. At Spock’s burial at space, in the movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, Kirk’s eulogy said of Spock, “Of my friend, I can only say this: Of all the souls I have encountered in my travels, his was the most . . . . human”. I bawled like a baby during that scene in the Paramount theatre on Jasper avenue in Edmonton. The point, however, is that once human beings empty ourselves of emotion, base our lives and actions on reason and the benefits of technology, we will achieve utopia. Kevin Cawley at Notre Dame University has made a recent case for philosophical apathy and its benefits to humanity in his article “What the World Needs Now”—and this is a characteristic of both Spock and Data in Star Trek.

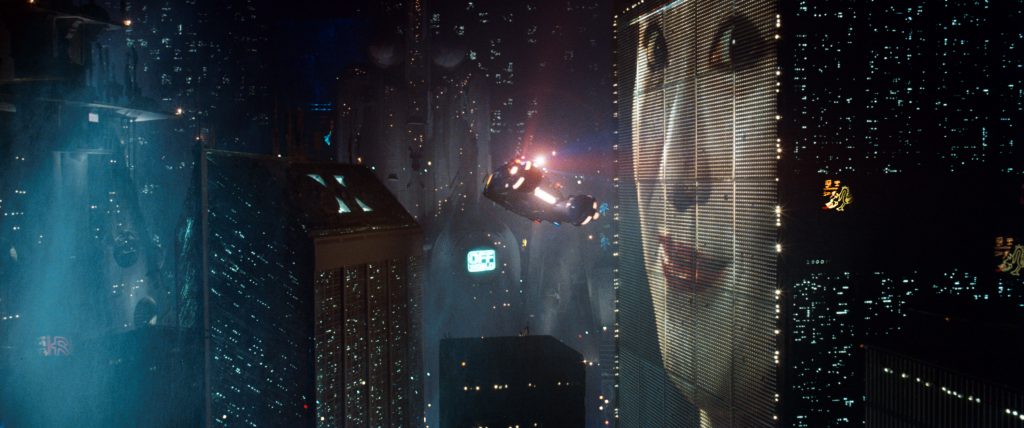

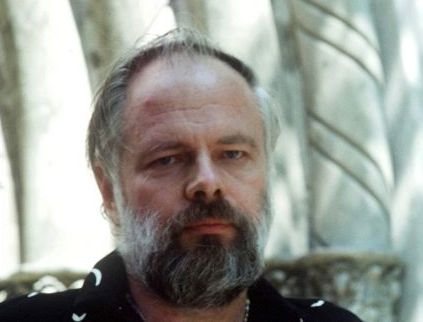

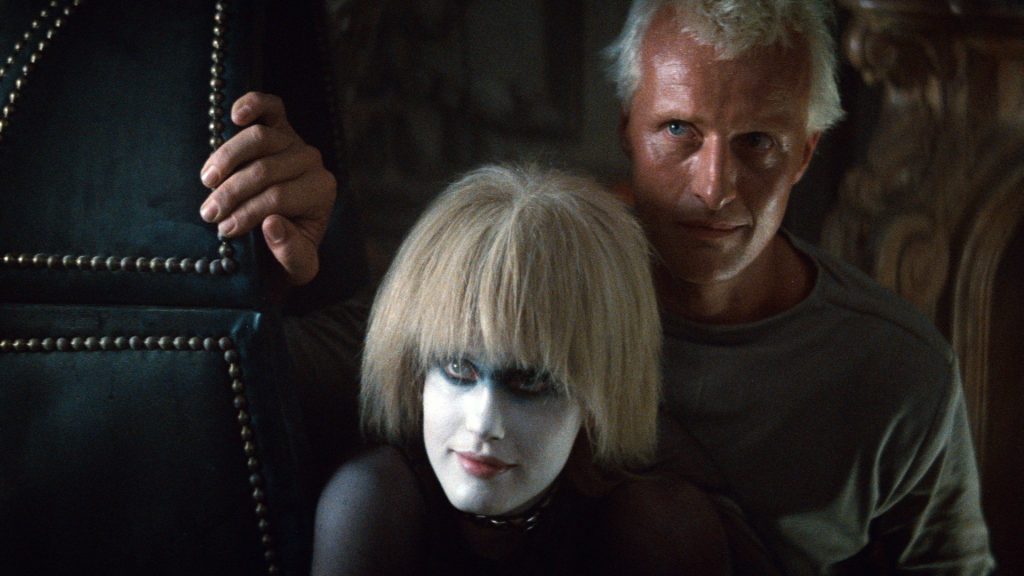

Enter Blade Runner (1982). Phillip K Dick’s book Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? was the basis for the Ridley Scott film Blade Runner which presented the opposite perspective on the rise of technology. Instead of technology leading to Utopia, it will lead to Dystopia. Of course, much of the contemporary pop culture reflects postmodern philosophy and the radical scepticism and pessimism (cynicism) inherent in it.

Phillip K Dick was also a complex human being with a complex relationship with technology and theology. According to Ridley Scott, Dick was a “Prophet of Science Fiction”—and his influence in the work of Scott is evident in many of his films, as well as many other science fiction movies. Scott, however, is much less sympathetic to religion and especially Christianity than Dick—who was a well-known Christian mystic. Scott, however, while growing up in the Church of England and being an altar boy, is no fan of organized religion nor the God of the Old Testament. Indeed his movie Prometheus is his own portrayal of a mean and vindictive Creator God paralleling Genesis 1-11 (see “Furious Gods: Making of Prometheus”); much in the same way he portrays God as a “mean and vengeful little kid” (Scott’s Theology Proper) in Exodus: Gods and Kings.

Scott is also well-known for his obsession with origins and religion—including that fact that the main character in Prometheus is a devout Christian—namely Dr Elizabeth Shaw. In Prometheus there is a clear juxtaposition of technology and theology (faith).

Back to Blade Runner. A theological summary of Blade Runner is a formidable task. I spend three lectures on it in my pop culture course. Blade Runner’s dependence on Frankenstein and Paradise Lost are well-known in relation to Genesis 1-3 (see Desser “The New Eve: The Influence of Paradise Lost and Frankenstein on Blade Runner”). The big theological questions and problems which are explored in the film relate to Theodicy (“Justice of God”) and Predestination vs Freewill; among a number of others.

Burnette-Bletsch, in the Bible and Cinema, provides a broad context for Blade Runner (like Paradise Lost) wherein these theological struggles are worked out in a veritable hell reflected the opening sequence of the film. Like Shelley in Frankenstein, Burnette-Bletsch points out, Blade Runner portrays God the Father Creator as an arrogant scientist who blames his creatures for evil rather than taking responsibility for creating them as such with built-in limitations like life-span. There is a tragic quality whereby God’s creatures desire to seek the Creator and their origins, as well as have a relationship with him, yet hate and blame God for creating them and placing them in an impossible situation. Thus like the monster in Frankenstein, Batty hates and kills his creator, the corporate giant Dr Tyrell.

The primary theological question explored by Blade Runner is: What does it mean to be human (Theological Anthropology)? This is where technology intersects with theology in terms of Artificial Intelligence, consciousness and sentience. If Roy and Pris as replicants are in fact conscious and sentient, as their behavior seems to demonstrate, should we be killing (“retiring”) them? Theodicy again raises its head in relation to predetermined capacities and limitations by which humans or replicants are imprisoned—an issue which the Apostle Paul addresses in Romans 9-11—which still needs to be taken seriously.

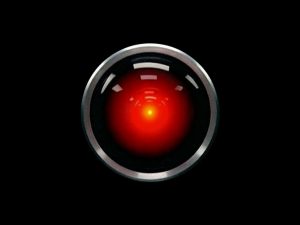

The issue of what it means to be human is also raised in 2001: A Space Odyssey in relation to HAL, Artificial Intelligence, consciousness and sentience. My friend who is an IT genius that managed a 110 million dollar IT budget argues vehemently that computers will never be able to achieve consciousness and sentience for one very simple reason: Programming does not make for “soul”. HAL is programmed that the mission to Jupiter is primary and any attempts to undermine that mission must be dealt with effectively. Therefore, if feigning emotions such as sentimentality and fear of death (unplugged) accomplishes that, then HAL will employ it. On this basis, I said to my philosopher colleague that Ontology should be the hottest thing in philosophy dealing with technology, AI, consciousness, sentience and transhumanism.

Another interesting contrast of technology comes by way of the collaboration of Arthur C Clarke and Stanley Kubrick in writing the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey. Clarke, in the documentary 2001: Making of a Myth, articulates a positive view of technology leading to Utopia (modernism). Kubrick, on the other hand, was afraid that man would lose control of technology in “Cain-like” destruction (so Burnette-Bletch in Bible and Cinema). This is, of course, the major premise of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. So far this century, dystopia is winning in the war between technology and theology in the larger philosophical context of postmodernism and expressions in science fiction.

My twenty-one year-old son Liam is kind of fed up with the whole dystopian image of the future of technology. He is studying Computing Science at the University of Alberta. He’s his own man who does his own thinking and is hyper-aware of cultural influences. So I think it’s only coincidental that he agrees with Telus that “The Future is Friendly”. Having said that, I think Liam is too grounded and realistic to buy in whole-heartedly to that slogan and rather has a balanced case-by-case approach regarding the future of technology. Given the ubiquitous dystopian view of technology in pop culture, however, I think that this tagline is one of the most brilliant marketing and advertising ploys. It speaks to the widespread fears of people in relation to technology and has a “disarming” effect. Of course, that’s how they sell technology. My son Liam’s view is more measured and grounded based in faith and reason: Technology has the potential for good or evil—and that is as fickle as Fallen Humanity—as well as being subject to the Will of the Living and Sovereign God.

Like a lot of people, I have a love-hate relationship with technology. Most of my professors used typewriters to write their PhD theses. That was a daunting task since just one typo meant that you had to re-type the whole page. So I was very grateful for technology when I got a computer to write my own doctoral thesis. I could not imagine writing a doctoral thesis without a computer with Spellcheck and especially “Find and Replace”. Now as a researcher, I cannot image life without the internet. Having said that, I do not allow internet sources in all my courses except for those in the discipline of Pop Culture Studies. One learning objective in all those courses is “How to vet internet sources for veracity, quality and substance”.

I ban all technology from my classrooms. It’s not because I’m anti-technology, or I don’t think that technology doesn’t have amazing educational value. It’s just that I have learning objectives beyond formal academic ones. One skill I want students to learn is the “Art of Being Present (Listening)”. Have an existential encounter with your dinner rather than taking another meaningless selfie of it. Moreover, you might just have a thought during the lecture that you would have been otherwise distracted away from if you hadn’t been “switched off”. Another is to think about the “role of technology” in your life: Should it be ubiquitous and eternal? Another is the utility and value of any given piece of technology: Is it just easier to manually do something like writing a note with paper and pen? Countless students who hated the policy to begin with have thanked me when they realized the many benefits over time including better grades.

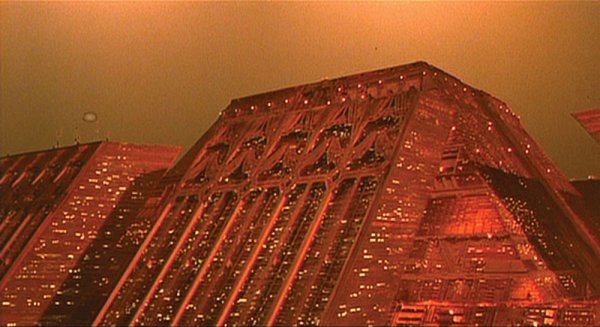

The Tower of Babel in the context of the Primeval History of Genesis 1-11 has a callback to Genesis 3. The Fall in Genesis 3 is where the essence of sin and separation from God can be found. The essence of sin is this: Pride leads to a false sense of not needing God the Creator and to Rebellion against him—that we can become “god-like” and make our own way. This is the same pattern found in the Tower of Babel narrative of Genesis 11.1-9. The message of Blade Runner is that ultimately humanity will save themselves through technology—but it’s a message than runs squarely against biblical revelation—and the triumph of God in the apocalypse. Ironically, the film intuitively undermines and succumbs to its own premise: technology does not lead to utopia but rather dystopia.

It is no coincidence that Ridley Scott makes a callback in Blade Runner (1982) to the explicit Tower of Babel image in the 1929 classic Metropolis. As I have mentioned before, Scott’s obsession with religion is well-known and the parallel to the God of the Old Testament (Genesis 1-11) is explicitly acknowledged by him for Prometheus—a deeply theological film (albeit of a skewed slant in my view). Alien Covenant, the follow up to Prometheus, is perhaps even more theologically explicit. What I would have suggested to Scott for his follow up to Prometheus was a focus on the Tower of Babel. It’s where Scott ends inevitably and intuitively ends up in both movies. If one examines the religion of the Ancient Near East, it is clear that the gods and their social structure are human. That is, we make God in our image rather than accepting God as he is: “I Am Who I Am”.

Humans are doomed to the bondage of slavery under the tyranny of a few divinely favored as represented by kings in the ANE and postmodern owners of huge companies like Tyrell or Weyland. Indeed, it is no coincidence that Tyrell also lives in a veritable Tower of Babel (ziggurat). Ultimately a life built without God (including a properly revealed version of him) is a dead end.

Even if we discover our origins, without a recognition of our sin and separation from God, life is as futile as using technology to build our own way to heaven and eternal life via transhumanism. As I have already noted, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Transhumanism raise questions about what it means to be human. What is consciousness? What is soul? What are life and death? Can technology really give us eternal life?

Transhumanism is another futile attempt to usurp God and save ourselves through technology. Its fatal flaw, even if we can upload our consciousness into a cybernetic body, is that it is still subject to the fragility of human beings living in a fallen world. We know very well just how fickle the economy can be in this century and how quickly mega-corporations can collapse. What happens when companies who manufacture parts go belly up or maintenance technicians can no longer be found? Moreover, eternal life without God can never provide meaning and purpose for simple existence and perpetual meaningless activity. As a theologian myself, even if AI achieves consciousness and sentience—it will be subject to the effects of the Fall in Genesis 3—and consequently will be in need of salvation (cf Romans 1).

Theology is in a unique position to handle these questions and issues. Indeed my MA student and Research Assistant, Erin Archer, has written a brilliant paper dealing with “Does AI Have Soul?” In that paper she argues that theology is in a unique interdisciplinary position to deal with the many issues, pro and con, that technology raises. She points out that theologians like Origen in the 3rd Century and Aquinas in the 13th Century made forays into Artificial Intelligence and surrounding issues—even if they didn’t know it at the time. So Theology has a big head start dealing with Technology.

Erin is currently writing her MA thesis on Religion in the Video Game Mass Effect under my supervision. This is another platform to explore AI, Sentience and Machines—or the relationship between “Technology and Theology”. The Geth are hated enemies in the galaxy and the cause of much death and destruction. But it’s more complicated than that—because the Geth appear to have souls—and much of their actions arise out of being treated like impersonal things (machines). One blogger, Tonio Loewald goes so far as to ask: “Would Jesus Save the Geth?” at https://loewald.com/blog/2012/04/would-jesus-save-the-geth/. Mass Effect is a case in point of how science fiction is used to raise all kinds of philosophical and religious questions and issues. As a Role Playing Game (RPG), this platform forces the player to engage with complex and important questions and issues that technology raises—whether they know it or not. Therefore, the video game format is interactive rather than passive. This amps up philosophical benefits to the player and consequently the value to society.

My own view is that technology is a gift from God for which I am deeply grateful. Indeed, in my own week-daily prayer liturgy, I praise and thank God “for science and technology—which show us more and more of His Glory day by day”. But technology is developing faster than our moral capacity to deal with it. Theology is in a unique position to handle the issues.

The Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith at Concordia University of Edmonton cordially invites you to our eighth annual conference. The theme for 2019 is Technology and Theology. The keynote speaker is Dr Craig Gay from Regent College in Vancouver BC. The title of his lecture is “Downsized: Modern Technology and the Diminishment of the Human”. This lecture is open to the public and FREE on Friday 03rd May 2019 at 7pm, with reception to follow, in the Tegler of Concordia University of Edmonton 7128 Ada Boulevard.

This conference is presented in collaboration with the Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence Research Cluster at CUE. There will be a panel discussion on the Saturday dealing with these matters. Please register at https://goo.gl/561nKf. Post-Secondary students are eligible for a free grant to attend at https://www.ccscf.org/conference/grant/ and there are also grants for pastors at https://www.ccscf.org/conference/clergy-grants/.1

]]>Reflections at the Beginning of the Reformation Year 2017

John A. Maxfield

Associate Professor of Religious Studies, Concordia University of Edmonton

Spring 2017

Google “Reformation 500” and links to multiple webpages appear, detailing local and global events focusing on the five hundredth anniversary of the beginning of the Reformation. The Lutheran World Federation, an international ecumenical federation and communion of many (but not all) Lutheran church bodies, has been gearing up for this anniversary jubilee for the past ten years. Five hundred years is a long time by almost any measure. Civilization, scholars generally agree, began about five thousand years ago in Mesopotamia and along the Nile in Egypt, so the past five hundred years marks a tenth of the span of human civilization. Christianity, the world’s largest religion, has endured for just over two thousand years if one marks its beginning with the proclamation of the apostles that Jesus was crucified not just as a victim of Roman brutality but as a divinely given sacrifice for sinners, and that God raised Him from the dead to live and rule as Lord. So the Reformation marks the most recent quarter of the history of Christianity.

Today, and indeed for the past four hundred years, the beginning of the Protestant Reformation has been celebrated on the annual date of October 31st, the date (the eve of All Saints Day in the Church’s marking of time) Martin Luther is said to have nailed to a church door in Wittenberg, Germany the Ninety-Five Theses, more properly titled Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences. Some skepticism has emerged in recent generations regarding the evidence for that event of nailing his theses to a church door, often portrayed (since nineteenth-century Romanticism) as the heroic if not rebellious action of a German monk, hammer in hand and with a crowd looking on with fascination. But there is no doubt that on October 31, 1517, Luther mailed (“posted” in a different sense) his disputation theses to the Archbishop of Mainz, that either that day or soon after Luther also sent his proposed debating points to his more immediate ecclesiastical supervisor, the bishop of Brandenburg, as well as to several friends and humanist scholars he thought might be willing to respond to the questions he was raising, by letter if not in an actual debate. There is also no doubt that the Archbishop, after finally receiving them in late November, sent Luther’s disputation theses to the papal curia in Rome suggesting that perhaps there should be an investigation; that Luther’s theses and the reactions to them soon created a curfuffle in the Church; and that within the next year formal heresy proceedings would be initiated against the Wittenberg friar and Doctor of Theology. Finally, it is a matter of fact that in the aftermath of this “Luther affair,” which formally ended (as far as the Church’s papal hierarchy was concerned) with his excommunication on January 3, 1521, Luther continued to be protected in his homeland while his ideas for the reform of Christianity slowly began to be implemented in many localities, first in German-speaking areas of Europe and then more broadly, all in the face of the Church’s condemnation. With his genius for communicating in the German language, making use of the technology of printing, Luther became the most popular author of the century and the spread of Reformation ideas became the first mass-media event. By the end of the 1520s the Reformation was taking root, and usually a local church jurisdiction would celebrate the event annually on the date the reform was formally introduced in a given region. Beginning in 1617, such annual were generally held on October 31st, thus acknowledging Luther’s raising questions about indulgences as the catalyst that began the Reformation.

But what of it? In a modern world that appears to continue on a path of secularization (at least in the West) that began with the French Revolution over two hundred years ago, what is the significance of the Reformation? Indeed, as historians seek to make sense of world history and engage in the abstraction of defining major movements and historical periods, the modern world with its values of freedom, equality, and tolerance is usually viewed as beginning with the eighteenth-century Enlightenment and not the sixteenth-century Reformation. The period in West European history once celebrated as the Renaissance and Reformation now usually goes by the rather bland name “early modern.” Even if the era is recognized as a period of significant transition, among historians of European culture (wherein the Christian religion played such a significant role) the Reformation is often viewed not primarily as a time of progress and flourishing but as a time of tragic conflict and division. That hardly seems worthy of celebration, much less ten years and more of marking the occasion.

History, that is, the narrative (or narratives) of the past, is most often written more-or-less chronologically, with the passage of time marking various developments, usually analyzing relationships of cause and effect. But the questions posed by historians are generally posed from the opposite direction, looking backwards. Historians frequently are seeking to answer questions that betray their opinion of the present—roughly either “How did we get to this wonderful time in which we live?” or “How ever did we get into this mess?” While historians mostly scorn the “Whig interpretation” of history that once fashionably traced the (wonderful) development of the British system of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy, historians of various ideological convictions still (one might say with increasing fervency) raise questions about the conditions that caused the rise of (intolerant) monarchical absolutism; or the liberation of modern, Western women from the shackles of patriarchy; or the emergence of tolerance from the bigotries of the past; or the rise of international terrorism inspired not just by political aspirations or oppression but by religious as well as political fanaticism. Views of the Reformation among historians today include viewing it as a cause (ironically via a religious revolution) of modern secularism, as a movement of rationalization or “disenchantment” of the world (though only partial—Protestants still believed in a God who intervened in human history but rejected the Roman Catholic traditions of the saints doing so), as the first major (failed) revolution of the Common Man against social hierarchy and economic injustice, as both the permanent division of the Western (Latin) Catholic Church and the long-awaited reform and further Christianization of that same Church.

If we view the Reformation along the lines of the goal of historical narrative according to one of its most outstanding practitioners from the past, Leopold von Ranke ((1795–1886), that is, not to judge its outcomes “for the instruction of future ages” but “merely to show how it essentially was,” we still can recognize in the sixteenth century an epoch of significant change, indeed one of the major transitions in the history of Western civilization and indeed the world. As his opponents pressed him in the aftermath of his theses on indulgences, Martin Luther eventually came to seek not just to reform the Church but to change Christianity. The Reformation did so, as large areas of European Christianity came to reject the papal governance that had ruled the Catholic Church for nearly a thousand years. That meant new structures of political authority and ecclesiastical authority, and for good or ill this meant changes in society and politics throughout Europe. And as European culture encountered the world in an age of discovery, it encountered that world in the form of a Catholicism invigorated in many ways by the challenges of its Reformation division, and in various forms of Protestantism, and all these manifestations of a changed European culture in turn shaped both the old world and the new.

]]>INDIGENOUS PEOPLE AND THE CHRISTIAN FAITH:

A NEW WAY FORWARD

So I’m a white dude. Ironic, I know, given the title of the article. I really struggled with the appropriateness of me writing this piece. One indigenous friend said it was “okay” to do so but he did chuckle at the irony of it all. So you’re still stuck with the white dude (again!).

So I’m a white dude. Ironic, I know, given the title of the article. I really struggled with the appropriateness of me writing this piece. One indigenous friend said it was “okay” to do so but he did chuckle at the irony of it all. So you’re still stuck with the white dude (again!).

Two of my favorite places in the world are Tofino British Columbia and Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump in southern Alberta. I have visited them many times. Both sites have been the home to indigenous people for over 10,000 years. That’s almost twice as long as ancient Egypt. I remember a wonderful experience with a young indigenous guy on the wharf of Tofino. He was talking with some tourists who were there and was saying how much joy he had being an indigenous person—relishing the most beautiful creation around him as his home!

Dances with Wolves in 1990 also made a huge impact on me. It made me think how beautiful indigenous culture is and how we Europeans messed it up. Later in the 90s, while doing my doctorate at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, I remember a very vivid memory of me standing the cloister looking at a poster for a North American indigenous art exhibit being held there. I remember feeling so guilty, and so a part of the problem, that I thought I should just stay in my ancestral homeland of Scotland. But without sounding like a psychological rationalization, my blond hair and blue eyes betray the fact that I’m really the product of 9th Century Viking raids into Scotland. Genesis 10, the so-called Table of Nations which provides the background for the nation of Israel, also makes the point that none of us are of pure genetic or ethnic uniformity. We are all migrants of mixed genetics and ethnicity—and that’s a good thing! This includes the fact that American (North, Central and South) indigenous people are from other geographical and ethnic backgrounds themselves. However, this in no way mitigates the inherent right of first peoples to this land. I also realized that there’s no “going back” and that we are all stuck with a complex situation. This is a point that my indigenous student will make later when I discuss his MA thesis.

Colonialism is a complex matrix of inter-related ideas such as philosophy, politics and economics frequently embedded in law eg the Indian Act. At the core of colonialism, in my view, is pride. It is a veritable “Tower of Babel”. It’s the arrogance and pretentiousness that one culture is superior to another—and therefore presumptively asserts its dominance over other people groups—while stealing their land and resources. This was often possible based on some form of technological advantage eg gun power. One should note, however, that Charles Mann in his book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus, has in recent years challenged this notion of technological superiority eg firearm targeting was not very accurate during this period. Mann further argues that European colonization had more to do with the “perfect storm” of circumstances—including plague and famine—which allowed Europeans to prevail over and against overwhelming population odds. In other words: There was no “superiority” involved but simply opportunity. Colonialism goes hand-in-hand with imperialism (sometimes these terms are used inter-changeably). My definition of imperialism is both simple yet essential: “Imperialism is killing other people and stealing their stuff”.

While I understand that some scholars like the African biblical scholar Musa Dube at Botswana University just view the Bible as colonizing, I view the problem as arising from the hermeneutics (interpretive strategies) applied to biblical texts eg colonial readings of biblical texts. This perspective can only entangle us in the past and provide no real way forward.

Postcolonialism is a theoretical perspective which “unmasks” and seeks to dismantle colonial power structures. I was first exposed to postcolonial readings of biblical texts at Glasgow University. Specifically I was exposed to South African biblical scholars who employed postcolonial readings of Chronicles-Ezra-Nehemiah to overthrow and deal with apartheid. In 1994, I was the secretary for the conference on “The Bible in Africa” (another irony). One black South African scholar made a presentation on a “Postcolonial Reading of Chronicles”. In that presentation, he demonstrated how a postcolonial reading of Chronicles may facilitate “truth and reconciliation” in South Africa. Twenty years later, I was able to suggest to my Master of Arts student, Charles Muskego, that he could do a similar thing as by using postcolonial readings in relation to indigenous issues here in Canada.

Charles is Dene Suline from Cold Lake Alberta. He wrote a brilliant MA thesis with me last year entitled Asserting Postcolonial Identities: Cross-Textual Readings of Ezra-Nehemiah and Indigeneity in Canada. There is no way that Charles could have written this thesis without his training as a biblical scholar and his three years of experience with Indigenous Relations in the Government of Alberta. The thesis is a masterpiece, in my view, of how biblical studies and theology can have actual, practical effects in the so-called “real world”.

Charles Muskego and Bill Anderson at CUE

Like Charles in his MA thesis, I am not going to recount all the horrific things that have happened to indigenous people—because all of that has been well-documented—and because we want to move forward. However, moving forward still requires a realistic acknowledgement of the past in order to deal with it and its fallout. Colonialism is what caused the mass suffering of indigenous people here in Canada, the Americas, and around the world eg Australia.

I find two amazing things about Charles. One, that he isn’t more angry with the past than he is. I think this is because of his Christian faith, realism, and determination to build a better future for his people here in Canada. But one can most certainly detect his annoyance at the Indian Act and Bill C-31 in places of his thesis. Secondly, I find it amazing that Charles did not abandon his Christian faith. Indeed, I’ve had the privilege to marry him and his wife, and baptize their children. Moreover, I find it astonishing, given the abuse that indigenous people have suffered via colonialism (and the wrongly applied version of Christian religion), that 65% of indigenous people in Canada remain Christian. This is almost twice the national average.

There are some other surprises in Charles’ thesis. He goes even so far as to be open and fair with the missionary movement—without defending their injustices. He views them as sincere but naively used for colonial purposes and agendas here in Canada by political powers.

Charles also gained insight into the complexities of indigenous issues by researching and writing his thesis. There are a plethora of first nations in Canada—and the issues are massively complex—with no “one size fits all” answer. So it takes this kind of research to analyze and sort the issues and problems out in order to come up with working solutions. This will be the focus of Charles’ PhD when he gets around to it.

The number one purpose of Charles’ MA thesis is to provoke a “new way of thinking” about the past, problems and issues. The significance of this MA thesis is precisely this: It shifts the focus from a negative past to a neutral present for a positive future. I’m sure that that positive future depends on a realistic perspective on the past which will give indigenous people a positive future through government policy guided by indigenous peoples’ asserting their self-identity and self-determinism. Again this is likely to be the focus of Charles’ PhD work.

The Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith conference for 2018 is on “Indigenous People and the Christian Faith: A New Way Forward”. I believe that this is a very significant conference for so many different reasons. Like Charles’ thesis, and without denying nor trying to mitigate a horrific past, we are stuck unless we move past the past. This conference acknowledges the real past but focuses on a “new way forward”.

We welcome all people groups to come and learn and think about how we can all work towards that goal—with love, forgiveness, truth and reconciliation. The conference is an opportunity to dream big and figure out ways to make it happen!

Our keynote speaker is Dr Cheryl Bear from the Nadleh Whut’en First Nation in British Columbia. She is a faculty associate with Regent College in Vancouver. She and her family, in a camper, have visited over 600 indigenous communities in both the USA and Canada. She is an award winning musician too. She will combine her scholarly and musical insight into how indigenous people can heal from the past, act today, and have a bright future with Christian faith. She has a passion to bring the gospel to indigenous people in culturally relevant ways.

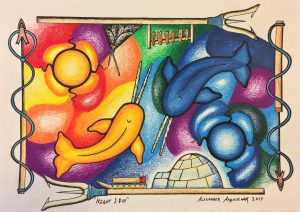

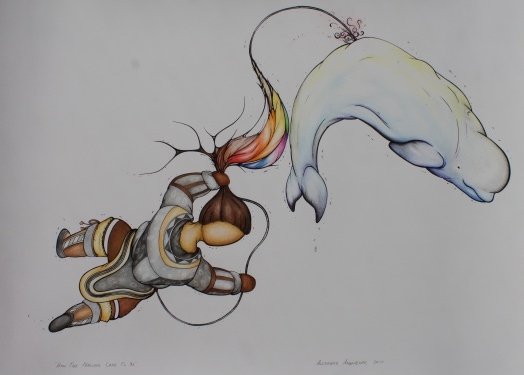

We will also have an exhibit and presentation by Alexander Angnaluak. Alex is Inuit and the Governor General of Canada’s recipient for the National Aboriginal Role Model award. He has received many other awards for his life and artwork—including the Historica Canada Indigenous Art Award for his impression of “How the Narwhal Came to Be”. The conference will also feature the artwork of many other indigenous artists. There will be lots of music and the conference will open with indigenous Christian worship.

Please register at https://goo.gl/imNeSJ. There are a limited number of Clergy Grants to attend free at https://www.ccscf.org/conference/clergy-grants/ and Student Grants at https://www.ccscf.org/conference/grant/. See you 4th-5th May 2018 here at Concordia University of Edmonton!

Rev. Dr. Bill Anderson is Professor of Religious Studies at Concordia University of Edmonton and the Director of the Canadian Centre for Scholarship and the Christian Faith.

]]>